I stood in the sandy northwestern edge of the Mojave Desert, a hot breeze blowing across my face. The temperature on an early afternoon in August approaching the triple-digits, typical for that time of year. In front of me, the mighty Sierra Nevadas tower above. Behind me, there is a patch of green, a garden, like an oasis in this desert. I feel a heaviness, one that sits in the core of my being. I am not sure if it is the spirits of the Owens Valley Paiute who had lived there for centuries before, before they were removed from their ancestral homes following the California Gold Rush. Or was it that 80 years ago, this deserted place would have had the bustle of thousands of people- of their sadness, worries, pain, and even joy?

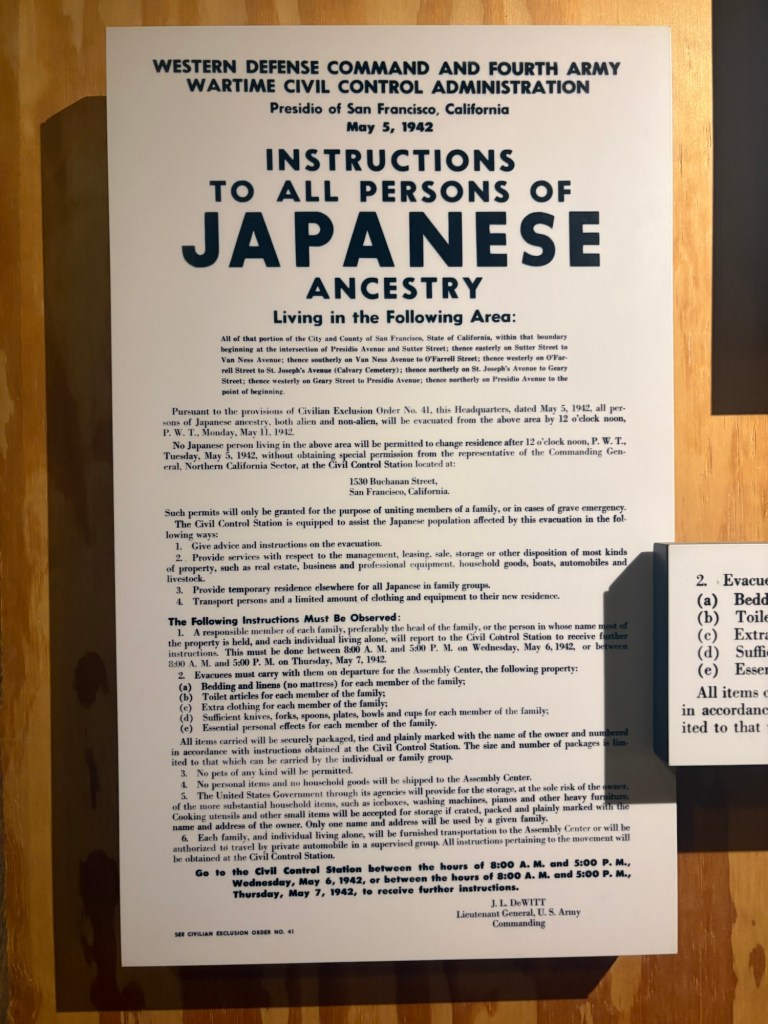

Just outside of the town of Lone Pine California, Manzanar National Historic Site stands as a reminder of Executive Order 9066, signed in 1942 by President Franklin Roosevelt following the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The attack had intensified existing racial prejudices against Asian-Americans that had been growing since the late 1800s, and fear of betrayal and espionage fueled anti-Japanese sentiments, especially on the West Coast. The move to ‘relocate’ families of Japanese ancestry happened very quickly; the executive order was signed just three months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

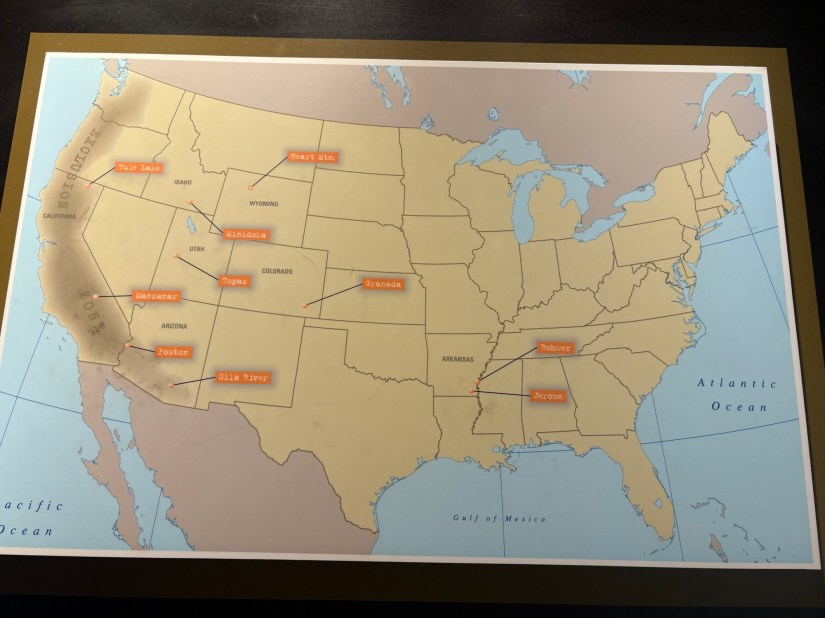

Arguably, while there is not one single cause to the removal of Japanese-Americans from the West Coast, the purported catalyst to the signing of the order was an isolated attack by a Japanese submarine off the California coast near Santa Barbara, and the resulting media hype over the ‘Battle of Los Angeles.’ This sensationalized accounting of events played into public support for mass removal. Thus, within just six months of the order going into effect, over 120000 people of Japanese ancestry living in the exclusion zone were sent to ‘War Relocation Camps’ across the United States. Owens Valley received 10046 individuals, and in those numbers were counted families, women, and children.

I cannot count the number of times I have driven past the turn off for Manzanar along U.S. 395 while on the way to Bishop or Bridgeport or Yosemite. I have often felt that we should pay a visit, to learn about the history of the Japanese internment, glossed over in many a history text, if even mentioned at all. We finally did so on the way home from Mammoth this past August.

We started our tour at the visitor center, which was once used as the camp’s auditorium, and today adapted as the site’s interpretive center. The camp was designated a national historic site in 1992 to ‘provide for protection and interpretation of historical, cultural, and natural resources associated with the relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II.‘

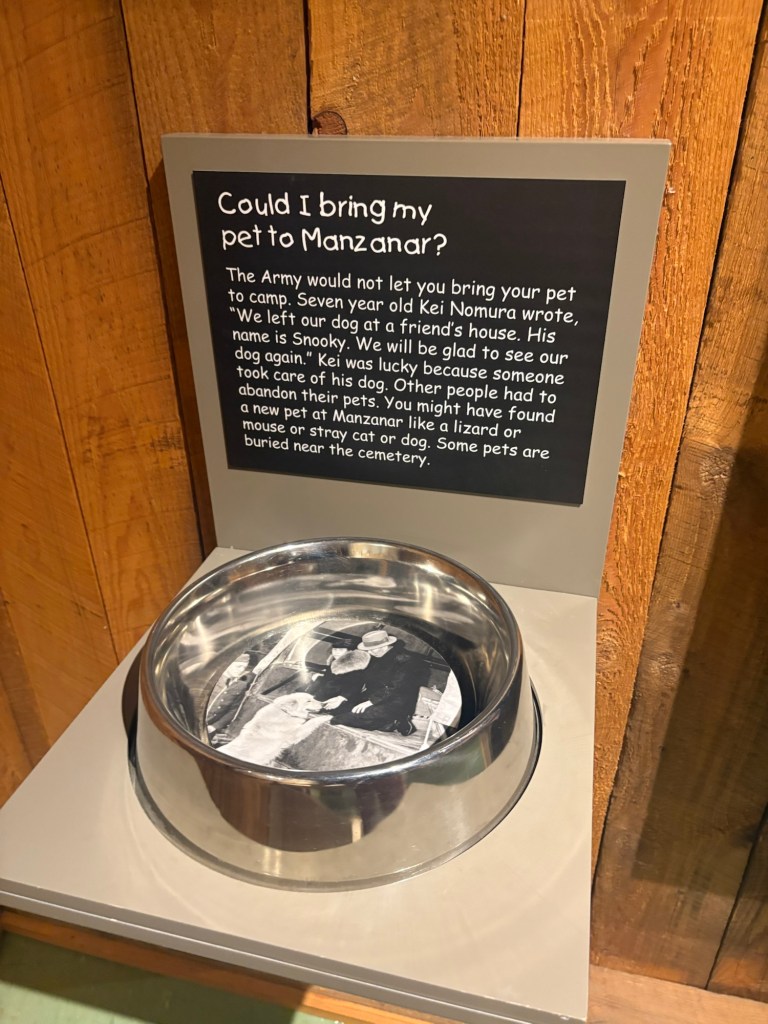

Life at Manzanar was harsh. The 10046 individuals were divided among 504 barracks in 36 blocks. Eight people shared a 20 by 25 foot cell, with shared men’s and women’s bathrooms and little privacy. The internment camp itself was closed in by barbed wire and guarded by eight watchtowers, patrolled by military police. Over the next three years, life continued, becoming routine for Manzanar’s internees. There were weddings. There were babies born. The Education Department at Manzanar started in 1942, with just a corner of a barracks. This grew over the next year, with 1300 elementary students and 1400 high school students enrolled in the Manzanar school. There was also an adult education program, which taught English, as well as classes in U.S. History and Democracy.

While the detainees made the best of an unjust situation, decorating their cells, establishing churches, organizing sports and social events, and doing life- they were not free to leave. In ways reminiscent of those detained at Oranjehotel, Manzanar detainees built furniture, created jewelry, and even started a newspaper. The Manzanar Free Press became the longest running newspaper in a concentration camp. Only the Manzanar ‘riot’ in December 1942, in which two were killed and ten wounded by military police, caused the paper to be paused for three weeks.

Then in 1943, the U.S. government administered a deeply divisive and controversial ‘loyalty questionnaire’ to Japanese-Americans over the age of seventeen held at Manzanar and other internment camps. The stated purpose of the test was to determine if individuals would be disloyal to the United States government. Special emphasis was placed on questions 27 and 28. Question 27 addressed the individual’s willingness to ‘serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?‘ Question 28 could be considered even more difficult: “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attacks by foreign and domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or disobedience to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?‘ To answer no would have meant removal to Tule Lake, a more restrictive, high-security segregation center. Some nevertheless did so as a form of protest.

And some Nisei- that is, second generation Japanese-Americans who were born in the United States- despite being unjustly removed from their homes and lives, did choose to serve. When the draft was reinstated for Japanese-Americans, many men joined the U.S. Army as part of the highly decorated 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated unit serving with the 100th Infantry Battalion in Europe. Others were a part of Military Intelligence Service in the Pacific Theater. Nisei women served in the Women’s Army Corps and the Army Nurse Corps. Despite discrimination, they served honorably, and made tremendous contributions to the war effort, with some paying the ultimate sacrifice. There were Gold Star families at Manzanar.

After reflecting on what it must have been like- to serve a country that treated one like an enemy or worse yet, to lose a child fighting for the country that was holding the rest of the family behind barbed wire- we headed outside. We got back in the Subie to take the auto tour of the camp. While much of the camp has been disassembled, there are still a few buildings left standing or have been reconstructed to give a sense of what life was like eighty years ago.

We followed the road, passing a baseball field and the site of what was once the Catholic Church. We turned and headed north, coming to the orchards and a beautiful little park. A literal oasis in the desert environs, Merritt Park was designed by Kuichiro Nishi, a detainee, and floriculturist Tak Muto. The park served as a place of rest and beauty for detainees as well as staff, a place of comfort in the harshness of the unforgiving Mojave.

After walking around Merritt Park, we followed the road up to the cemetery. A large white obelisk, inscribed with ‘soul consoling tower’ stands as a monument to the lives lost at Manzanar, and also as a symbol of hope. Approximately 150 people died at Manzanar; most were cremated, but six graves remain at this site. It is a quiet place, pretty and serene, under the watch of the mighty Sierras. May the dead rest in peace, and may their memories live on in their loved ones and in history.

After paying our respects, we drove on, passing the foundations of barracks and warehouses. It felt like a ghost town in some ways, a testament to a history that should not have been- one where people were judged not on their character but merely on their ancestry, and the prejudicial assumption that being of certain descent meant they were a threat to national security.

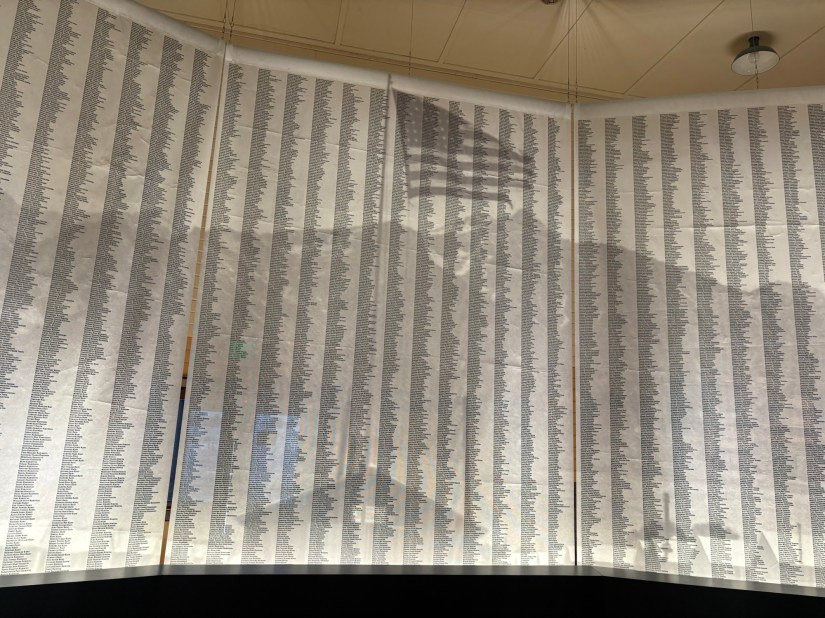

In 1988, the U.S. Civil Liberties Act granted survivors of the Japanese internment a payment of $20000 and a formal apology. President George H. W. Bush oversaw the payments and the sending of formal apology letters, and in March 1992, the president established Manzanar as a national historic site. The names of those who were interned are on display in the visitor center. So many names, so many lives forever changed by fear, distrust, and blind prejudice.

And perhaps this is the point. Over two-thirds of those incarcerated were indeed American citizens. People who had hopes, dreams, lives, and loyalty to the country they called home, were forcibly removed. Many of them owned homes and ran businesses. To this day, in the year of our Lord 2025, there has not been brought a single charge of espionage against any of those who were interned at Manzanar. The people who were forcibly removed from their homes and taken to ‘war relocation camps’ were done so without due process. The Constitution, which is supposed to protect all people on American soil, did not protect Japanese-Americans, even American citizens, living on the West Coast. And in 1942, as the United States faced the realities of a war on two fronts, it was not evidence and rationality that prevailed. It was anti-Asian hostility, fear, and media hysteria that ran rampant and brought over 10000 people to the harsh California desert in the rain shadow of the Eastern Sierras.

We must remember. We must remember this painful piece of our American history- as well as others- and we must learn from it. This post is about Manzanar and the lives that had been impacted by the injustice of the Japanese internment, and there is also a reminder that while history may not exactly repeat itself, it can and does often rhyme. We must not let fear win out. The United States Constitution will only be as effective as the government leaders and judiciary who respect and uphold it and as we the people who hold them accountable. We must never take for granted that freedom is only a generation- or even an election cycle- away from possible extinction. And may I opine that in this country, freedom for some is really freedom for none. May we remember- and seek justice, love mercy, and walk humbly- for liberty and justice for all.

To plan your visit, please check out the National Park Service website.

References:

“Japanese Americans at Manzanar.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 8 Aug. 2024, http://www.nps.gov/manz/learn/historyculture/japanese-americans-at-manzanar.htm.

Manzanar Free Press (Newspaper) | Densho Encyclopedia, 2025, encyclopedia.densho.org/Manzanar_Free_Press_(newspaper)/.

Loyalty Questions, http://www.du.edu/behindbarbedwire/loyalty_questions.html. Accessed 21 Sept. 2025.